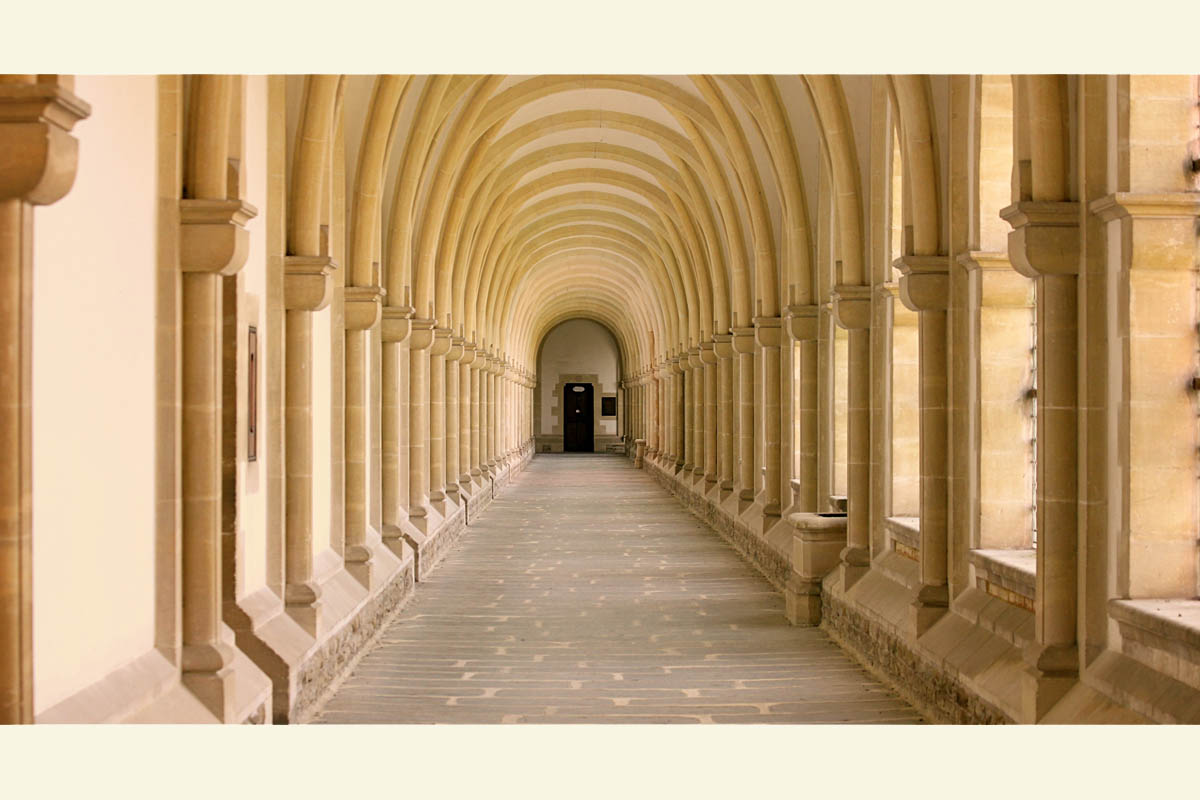

great cloister garth

church and cloister garth

“Jesus was led by the Spirit in the wilderness” (Lk 4:1)

At the centre of Carthusian life is the hermitage. The community life brings together a group of hermits. It is in solitude that the heart is deepened and inhabited. The hermitage is above all a place of communion with God and, paradoxically, with man. The monk is “never less alone than when alone.” Little by little his heart is enlarged to the dimensions of Christ’s love encompassing everything and every person in Heaven and on earth. Separated from all, he is united to all.

The main room of the hermitage is the “cubiculum”, in which the monk prays, studies, eats and sleeps. It is significant that he enters it by passing through an antechamber called the Ave Maria. It is through Mary that he enters into the tent of meeting with the Lord. Equally the Offices he prays in cell are always preceded by a prayer to Our Lady, the principal patron of the Carthusian Order. Her "Fiat" (Yes) to the action of the Spirit is the model of contemplative prayer.

“Our principal endeavour and our vocation are to devote ourselves to the silence and solitude of cell. This is holy ground, a place where the Lord and his servant frequently converse, as between friends. There, the faithful soul is often united to the Word of God, the bride with her Spouse, earth is joined to heaven and the human to the divine. However, the road is long, and dry and barren are the paths that must be travelled to attain the fount of water, the promised land.” (Statutes 4.1)

church and cloister garth

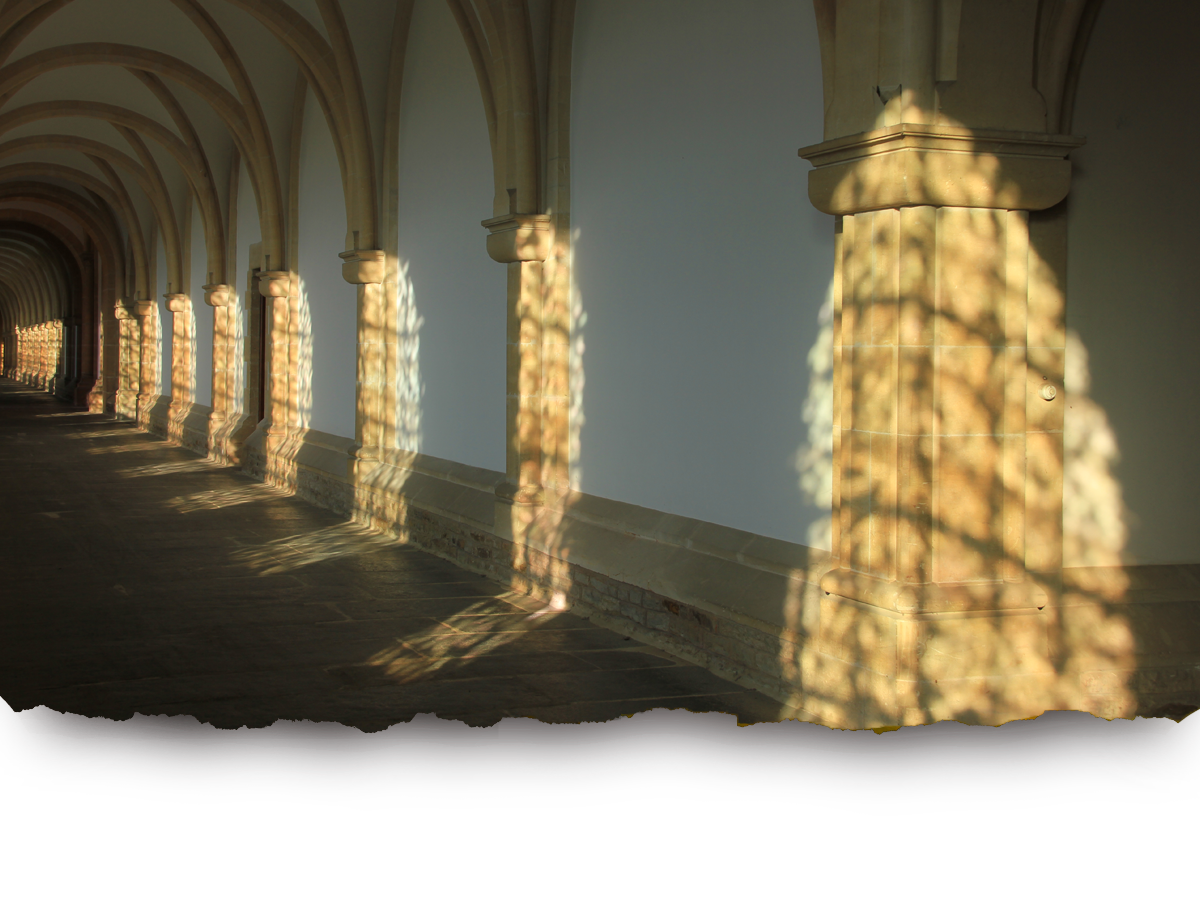

south cloister

great cloister

cell

none

none

none

none

none

none

gardening

The monk’s day is structured by the Liturgy of the Hours, the prayer of the Church, which he celebrates every couple of hours in his oratory. It is filled by simple activities designed to help him to live in the presence of God, to let God in by all the receptive capacities he has endowed us with.

“The more the monk has lived in cell, the more willingly will he dwell there, provided his time there is spent in a fruitful and orderly way, reading, writing, reciting psalms, praying, meditating, contemplating and working. During this time, let him accustom himself to tranquil listening with his heart, which allows God to penetrate it by all ways and all means of access.” (Statutes 4.2)

Manual work in cell and, for the Brothers, in the Obediences (kitchen, laundry, garden, etc.) are important elements of balance and service, and occupy a few hours daily.

Silence is the air the solitary breathes. The monastic tradition called it “the language of the world to come”. From being an exterior discipline, it is gradually interiorised, a mystery of communion with the Trinitarian love that so surpasses our busy words and concepts.

“The fruit that silence brings is known to him who has experienced it. At the beginning of our Carthusian life, to keep silence requires an effort; however, if we are faithful in this, little by little, of our silence itself, something is born within us that draws us on to greater silence.” (Statutes 4.3) Ultimately our silence becomes Word, the darkness of faith is itself the Light.

The goal of the solitary is unceasing prayer, that pure prayer which is the prayer of the Spirit of Christ in us: “Abba, Father, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven…”

“God has led us into solitude to speak to our heart. Let our heart then be like a living altar, from which pure prayer ascends constantly towards the Lord, permeating all our acts.” (Statutes 4.11)